It takes something of a village to sow and tend and cultivate young sprouts till they’re full-grown and verdant; it takes tilling and toiling in summer and winter, springtime and harvest, patience and a love that’s tough as nails yet deeper than soil. I come from a village of an assortment of folk—teachers and tradesmen and musicians and homemakers and vegetable growers. My grandfathers were (are) men of the land and their wives, my grandmothers, proud to stand by them in every season.

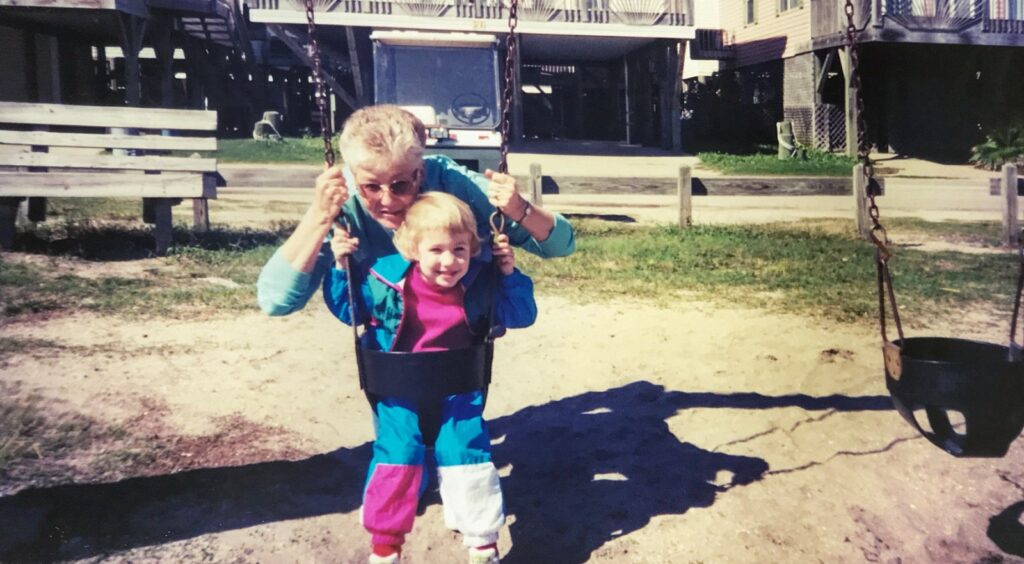

On my mother’s side, I was the first of four grandchildren to be welcomed into the fold, embraced by rolled-up sleeves and the will of a pair of southern gardeners toiling beneath a summer sun, gracious participants in tending to a set of fragile, newly propagated roots. They made it look so easy, as if they’d always been tailor-made for exactly that task, and it for them.

Their white and blue-shuttered farmhouse sat atop a knoll just beyond the city limits, flanked by a pasture of grazing horses, linens swaying on clotheslines and yellow meadow flowers that erupt in spring and give way to towering hay bales come autumn. The screened-in porch just off the kitchen has been home to a dozen windchimes that always seemed to carol loudest on a sunlit afternoon and decades of just-because barbecues where cousins rode bicycles in the driveway or started a game of baseball in the yard; after dessert—usually Neapolitan ice cream or some variety of pie—we’d always walk the path to the barn to rub the horses’ velvety noses and supply the donkeys and goats with stale bread and sugar wafers.

Warm weather meant every window in the house would be propped open upon our arrival, and brisk autumn days signaled a free-flow of black coffee and hot apple cider. We’d almost always find her in the kitchen, my grandmother (Mawmaw, as my generation knew her best, or Lois—she answered to both), slicing tomatoes and cucumbers for a garden salad or popping a pan of dinner rolls into the oven.

We lost her last September, not to the COVID-19 pandemic but to the cruel and drawn-out crescendo of dementia. When I think of it, we’d already lost her three years prior, when short-term memory grew fuzzy like static on an old television set, pictures all disjointed and noisy. The summer of 2017—watering the flowers and plucking tomatoes from the backyard vines—is the last true memory I have of her. The rest of them, attendants of a recurring wake, gathered to mourn the loss of what used to be.

In their post-retirement prime, my grandparents were a pair of explorers discovering North America one bus trip at a time, minting their expeditions with postcards sent from Nova Scotia and Daytona Beach, and snapshots from a cruise somewhere in the Caribbean. I wish I’d asked more questions when I had the chance, rummaged through the shoeboxes and albums packed with these mementos before she died.

Aside from these missing stitches in the fabric of her history, a gold bracelet set with assorted gemstones and the palpable void that now exists by the kitchen sink, in the garden and next to Papa at the dining room table, she left behind a sort of inheritance, one she passed down to me years before her passage from this life: an urge to find the world’s bright places and revel in them.

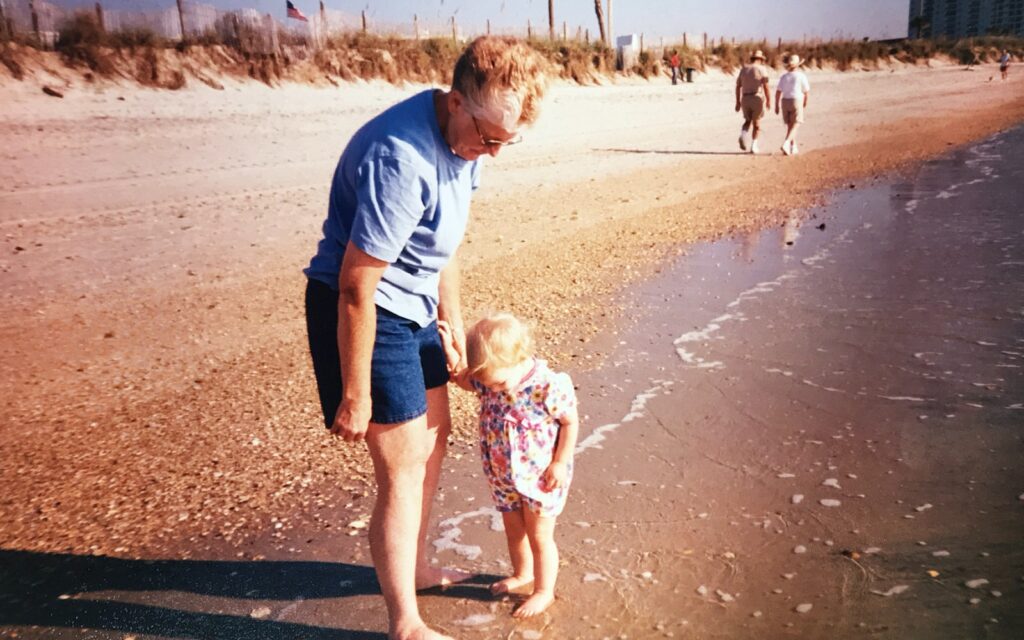

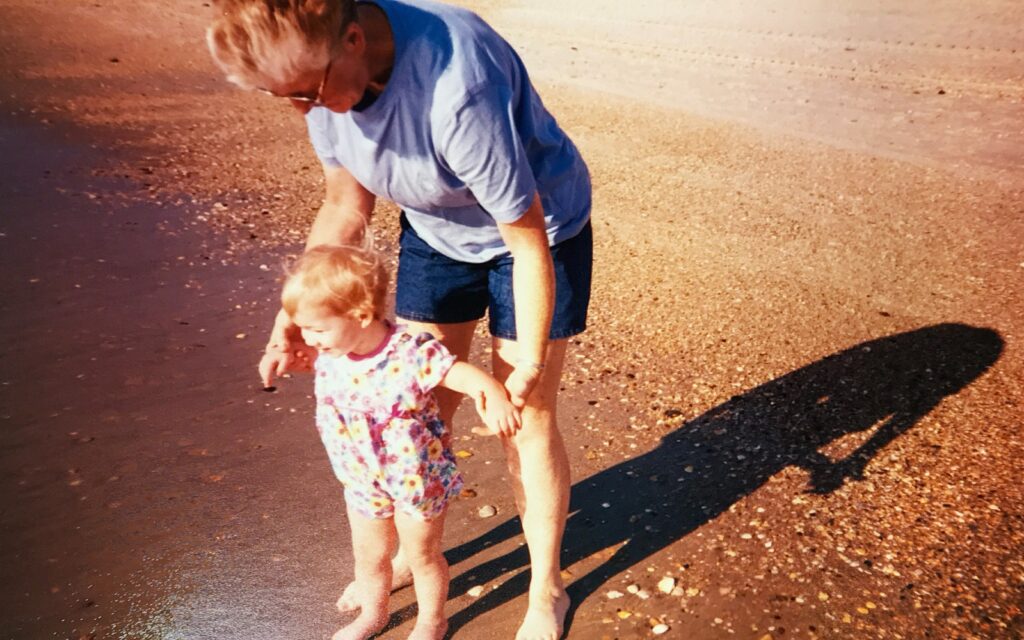

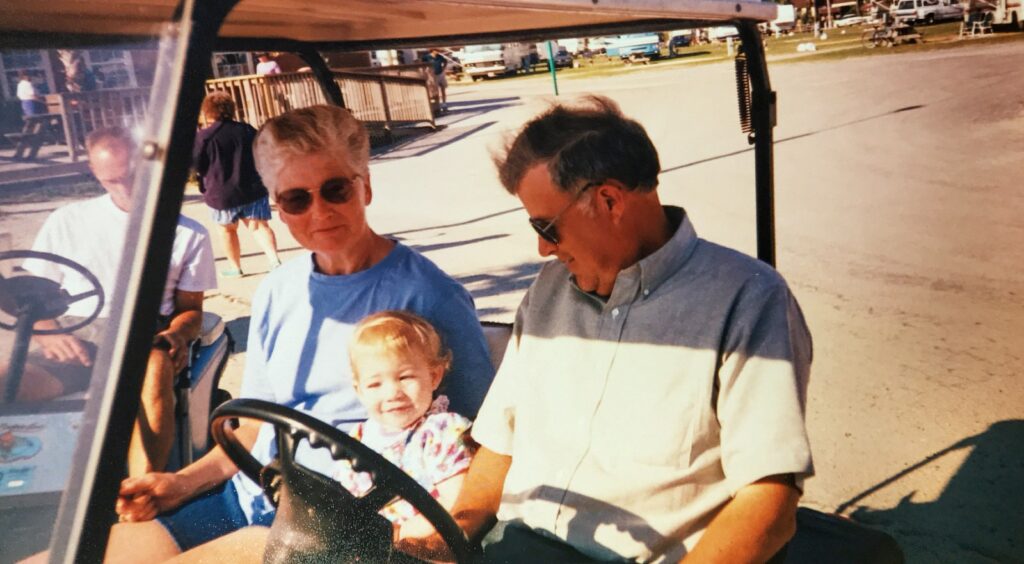

For my grandmother, Myrtle Beach shone brighter than any other place on the map. Several years in a row, she and my grandfather, my parents and I—and my sister when she joined the crowd—shared a little two-bedroom rental that always smelled of clean laundry, freshly brewed coffee and Honey Buns. The fragrance of nostalgia, welcoming me to waking each morning. After all this time, they’re still inextricable companions in my mind: Honey Buns and the Carolina coast. One taste of the pastry’s sticky-sweetness, one whiff preserved in plastic packaging and warm memories of childhood are conjured: Mawmaw offering me one first thing each morning, my small and sleepy voice always responding, “Yes, please.”

A tradition was minted in those moments, and even after we’d all grown older and financially stable enough to afford a handful of beach days on our own, we still stocked the pantry with Honey Buns as though they were just as essential as a canister of Folgers, the daily newspaper or clean drinking water. (They were.)

I think that’s why we never bought them for ordinary days in our own house; they weren’t ordinary snacks. Mawmaw kept a ration of them at the farmhouse, in the kitchen pantry next to the Oatmeal Creme Pies. “I like the way they taste with my coffee,” she’d reason, as if we needed convincing of what we already knew. Within a matter of minutes, we’d find our way to the screened-in porch, mug full of hot coffee in one hand and a Honey Bun in the other, transporting ourselves back to the little yellow beach house once more.

It’s been ages since I’ve sunk my teeth into anything boasting Little Debbie’s name, but time is irrelevant—that’s the magic of all the bright places and the near-sacred things they house. I tried to give words to it as part of a conceptual art assignment in college; I’m still not sure whether the three-lined poem that came out of it flowed from those pockets of time or because of them, but it’s stuck in my mind like a mantra ever since:

“Make the most of these days.

Soak them up and wring them out for all that they’re worth;

soon it will all be memories.”

Looking back, I’m glad we did just that.

February 2020

I’d just moved across the country a few months prior; my birthday was approaching and, having spent the bulk of the holidays crying alone in a one-bedroom apartment, I felt an insurmountable sense of urgency to return to Virginia, to my people. We’d reached the point in our dementia-thwarted journey where the next year’s landscape, how it would look and who’d be a fixture in it was anyone’s guess or gamble, the point at which every moment was more precious than the last. So I booked a red eye and told no one but my sister, who met me at the airport with a blueberry doughnut and toothpaste. She’d brilliantly schemed a way to get the four of our remaining grandparents (we were lucky enough to be born with five) to Mom and Dad’s for dinner, and the overlapping waves of surprise, momentary confusion and elation washing over each of their faces as they crossed the threshold into the kitchen rank among the greatest gift I’ve ever been bestowed.

The eight of us crowded around a table built for six, passing grilled chicken and cheesecake and witticisms between us till the night ran out. I wish I’d snapped a photo to preserve the moment and tuck it away for safekeeping, so I could remember with stolen glances the way it tasted, the way it felt, the way it was our own Last Supper of sorts and we didn’t even know.

But in the moment, that moment was all that mattered. And if I had it to do over again, I don’t think I’d change a thing.

September 2020

I sleepwalked between flight connections, shell-shocked and numb as a $600 ticket closed the 2,300-mile chasm between the farmhouse and me at what felt like a snail’s pace.

Everything else happened so fast—the fall that sent the dementia into overdrive, the six-week stint in the hospital and rehabilitation, isolated from face-to-face connection thanks to COVID-19 and an inpatient room without windows. Despite their shoddy phone system, my mother had the facility on speed dial; she called every day in hopes of chatting with my grandmother, a nurse or anyone who could give her an accurate description of how things were going that day, whether she’d eaten enough for breakfast, whether physical therapy was scheduled for morning or afternoon. Mom was so vigilant even in the distance that, as Mawmaw’s memory continued to wane like a sun-faded photograph, she was convinced that my mother was hers, too. It’s strikingly bittersweet, how innocently those tables turn.

“Dad” flashed across my caller ID on a Thursday afternoon and something about that time just felt different, like a premonition. Mere hours after the doctor insisted the months-long strand of time that remained was on our side, a medical emergency claimed it all in one fell swoop. No one got to say goodbye; no one even knew until Mom got the call, hours later.

The following days were a blur as I tried to get to the other side of the country while everyone else was already there, sitting down with attorneys and funeral directors, rifling through clothes and jewelry and old photographs, writing obituaries and making phone calls. We gathered on a hillside on the autumn equinox—one of her favorite days, appropriately enough—to celebrate a life well lived-in and loved-in and pay our respects to the lapse of seasons the author of Ecclesiastes 3 hinted at centuries ago, in our season of mourning breathing thanks for all the seasons of laughter and dancing that eighty years of life, sixty years of marriage, parenthood and grandparenthood could possibly house. The bright places, true to their luster despite the heavy blow that tried to dim them.

September 2021

September and I meet with a note of nostalgia between us; we always have. There’s an almost tangible bittersweetness to the air, the way summer folds seamlessly into autumn and seasonal ruckus slows to a more reflective tempo.

This year, the notes are overtones and I catch myself reaching for the phone on a handful of occasions, remembering mid-motion what I already know but somehow momentarily forget. Sometimes she’d call me on a Sunday afternoon, during a lull in the NASCAR race, or I’d call her and we’d chat about the days of our lives and the ways they’d unspooled since the last time we spoke. Sometimes I’d miss her call and she’d leave a voicemail, always calling me by name, almost always identifying herself although I already knew who it was, always telling me in so many words that I was on her mind.

“Happy birthday, Rachel, I love you.”

“Rachel, this is Mawmaw—I was just sitting here thinking about you.”

“Rachel, this is Mawmaw—just thought I’d call to say hi and see how you were doing.”

I have a habit of not tidying my voicemail box until someone alerts me that it’s full; I like having a way of hearing someone’s voice when I want to remember what it sounds like. These days, I find myself going back to the archive more often just to make sure the messages are still there, that they still sound the same, to feel the heartache and the gratitude dance together in three-quarter time.

It’s not just about the messages, but everything else that’s tucked into them.

The porch and the farmhouse and the jaunts to the pasture, the smell of Honey Buns and laundry turned out to dry.

The bright places, true to their luster even still.

BERNICE J ALEXANDER | September 19, 2021

|

thank you for your story! You have an amazing talent. Keep uncovering those gems!

Ramona Newcomb | September 20, 2021

|

Loved your story. Your mammaw was my 1st cousin. She and my mom always hung out together with mike and my dad. Your story brought back so many of my own memories. Thank you.

Bruce Wyrwitzke | July 13, 2022

|

Lovely story, Rachel. I seem to remember your trek east; you spoke briefly of it in “First Take.” My mother-in-law, “Mom” to me for 52 years will be 99 in December. FortunatelY for us, her mind is fine, but everything else seems to be paSt their pull date. We plan our calls for when we know she’ll “have her ears in.” Again, her mind Still remembers what we told her last week. Her still being “with us” keeps us young because we’re still somebody’s kids.