It had been four years since I’d visited Petrolia, California—a quiet town in a hillside pocket of the Pacific Ocean’s Lost Coast. One road in, and one road out, it’s a quaint town mostly unimpacted by the past four, hell, maybe five decades. Which is precisely why it’s so wonderful. And here I was once again, this time with dusty vinyl, a rack of lamb, and the possibility of dropping acid.

The town has a unified grocery-post-office-sandwich shop with an always-parked ‘60s VW Bug in one of its ten or so parking spots, one bar and restaurant, and two phone booths. It may be untouched by time, but it’s been quietly shaped by its quirky townsfolk who’ve called the place home over the years.

There’s little a wanderer needs in a landing place aside from a few welcoming locals eager to let you in on the town’s secrets—or at the very least order a round of tequila to liven things up—beer on tap, a place to rinse your feet—be it a beach, a creek, or a water hose—some good roads to journey by day and a good place to rest your head at night, and a decent sandwich, of course. Handshakes, watering holes, and picnic food do a traveler right. Petrolia has all the above.

There is also a vineyard—Lost Coast Vineyards—which happens to produce an award-winning Pinot Noir. Those who know me well know a glass (read: bottle) of Pinot is my preferred way to unwind. Nearby, you’ll find the turquoise mouth of the Mattole River where it pours into the Pacific at the King Range Wilderness—a surreal, windy landscape made up of white sand, green mountains, ashy driftwood, and enclaves of beach shrubs. Back in town, there is a chapel, an impressive Sunday farmers market, a handful of artists, and a local woman who handmakes organic bath products in her barn. Sometimes there’s a five-dollar pancake breakfast at the Mattole Grange, too.

Beyond that, Petrolia has captured the tales, estate, soul, and, occasionally, the daughter of a legendary and controversial author.

The porch was a museum unto itself, carefully curated by the late Alexander Cockburn—a left-winged political author, world traveler, philosopher, tinkerer, vinyl collector, and dog and bird lover—a museum overflowing with knickknacks from global treks, grapevines, tapestries, piano keys, fruit bowls, and cobwebs. Cockburn’s daughter Daisy says her father loved cobwebs because he thought they were romantic. So she hasn’t dusted since he died. These were his cobwebs, and I would spend the next three days metaphorically peeking through them.

I curiously and carefully inspected each fine detail before stepping through an open door into the kitchen. The estate kitty followed along. And then, of course, there was the house dog, Jasper—the fourteen-year-old, grey, arthritic, and happy remnant of Alexander’s life.

Loose photos sat fading on window sills. Pottery and hardback books aligned shelves. Caged songbirds sang along with the breeze as it floated through open doors. An old writing desk sat illuminated by sunlight pouring through paned windows. Typewriters, dirt-covered squash, lanterns, and perfectly aged throw rugs surrounded me. Dust particles floated gracefully down sunlit avenues, and I stood in awe in what felt to be the ghosts of Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Kerouac; they, too, were writers, adventurers, and lovers of the open road. I could picture them at this table with warm Scotch in tumblers, cards ready for dealing, prepared for heated discussions about politics, philosophy, and life.

Daisy was in her father’s art studio in the backyard, and greeted me with a chipper British accent, dressed in a well-worn, paint-covered apron, as I tiptoed through the open back doors. A yoga mat was strewn across a patch of grass beneath an apple grove. A small temple of sorts sat at the rear of the fruit trees, which housed Alexander’s cidery, with vats full of his handcrafted elixirs. I was sure I’d found some variation of a literary, antique-filled, botanical heaven.

The sun was setting, and we had to hike to the tower before darkness set in. It’s a short but steep climb following switchbacks up a hill lined by some of Alexander’s sculpture collection. Whimsical fish greet you at switches as you move onward to the top of the hill—where the treehouse-like tower overlooks more apple groves, evergreen forests, and provides a perfect view of the setting sun above apple-garnished treetops.

Times like these serve as reminders that every place we find ourselves and every person we meet serves some purpose or offers something to be discovered—be it a magical vista at dusk overlooking the Mattole River Valley or the friendship with Daisy that blossomed once we realized Timber couldn’t make it up the tower’s stairs after the hike uphill. He tiredly barked at the cabin’s entrance, two flights up, defeated by the limitations old dogs bear, while the sun fell below the treetops and was no more.

Knowing we’d otherwise be camping atop that hill beneath the apple orchard—and having a dinner of only plums being that the grocery was closed and making it back down the hill and to the town’s only bar would be impossible for Timber—Daisy invited us to join her for supper and to slumber at her father’s estate.

So, we ventured back down the switchbacks, back through the apple orchard, and into Alexander’s home where Timber and I would fill our bellies and rest our heads. The guestroom looked like a page from Hansel and Gretel. A hideabed piled high with ancient quilts was bordered by a suitably tethered Mark Twain collection, dusty spectacles, and antique lanterns. A crimson rug would be Timber’s bed, frayed edges announcing its long life.

Daisy began chopping garlic, boiling water, and pouring red wine. Before much time had passed, Timber had helped himself to a package of bacon; horrified, I warded him off as he growled at our lovely host. But she had a jovial spirit about her and found humor in his finicky old man sense of entitlement; my asshole dog wasn’t going to interfere with our pasta feast.

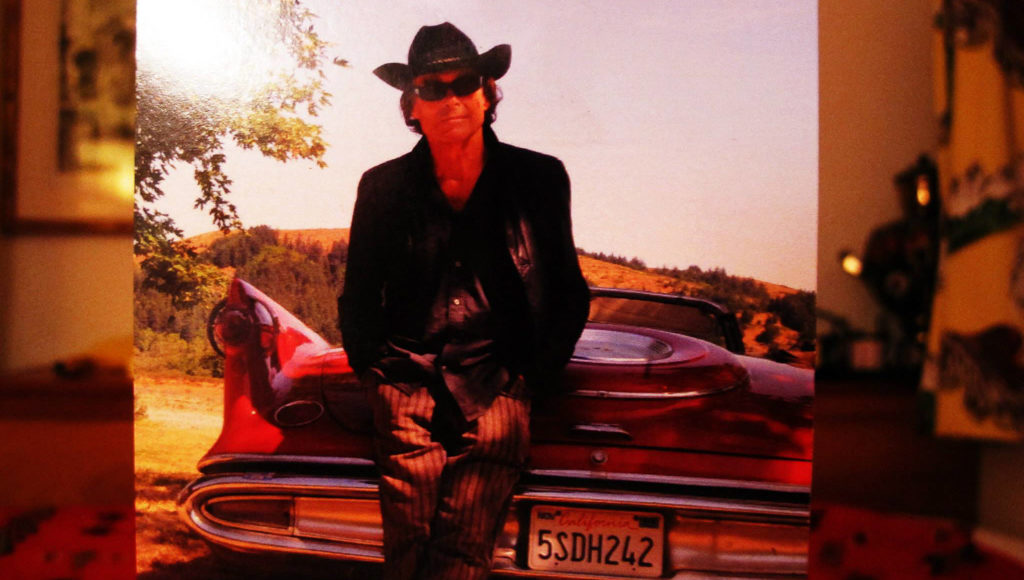

Our glasses remained full while Daisy told stories of her father’s travels, and of his friends, collection of classic cars, political feats, extreme ideologies, appreciation of music, love of adventure—and adoration of this quiet town. We drank more. And our inquisitive, wine-dampened minds moved onto conversations about our own travels, follies, feats, triumphs, lovers, and life desires. Daisy is an intellect, a scholar in her own right, and I found myself wondering what insights Alexander would have contributed to this conversation. Surely he’d have many.

I laid in bed that evening, flipping through a memorial edition of CounterPunch, the political publication Cockburn—alongside Jeffrey St. Claire—was well known for. I read the stories of those who worked and lived alongside Cockburn much of his life. Politically, we were a world away from one another, but from a journeyman’s, a writer’s, and a wanderer’s perspective, we were one in the same. His mind fell more and more to my intrigue the more Daisy spoke of him, and the more I museumed through his home. One particular excerpt from Jeffrey St. Claire in this memorial edition spoke numbers to me:

“If there was a deadline, he would run right up to it and often past it. This wasn’t because Alex had writer’s block, it was because he had better things to do, like feed the horses, teach his cockatiel Percy to whistle the Internationale, fix—or try to fix—the septic, prune the apple trees, tweezer out a deer tick from Frank the cat’s black dreadlocks, distill hard cider, check the progress of the pit barbecue, negotiate a complex Persian rug deal with Lawrence of La Brea or find his glasses.”

I awoke the next morning to hot English tea and corn flakes soaked in heavy cream. It was July 21, 2013. Unbeknownst to me, and as chance would have it, this morning marked the one-year anniversary of her father’s death. Daisy was hosting a traditional English dinner party in honor of her father that very evening; his best friends would be attending—including the local winemaker who’d become blameworthy for many wine-induced hangovers that would follow. She said it would be a pleasure if I could attend.

I returned to the house around sunset, the kitchen rich with festivity and the thick aromas of a British feast—roasted lamb, cabbage, and some kind of spiking hot fritters we passed around. The wine was pouring—none other than the Pinot I’d come to love—by none other than the winemaker himself. The eight of us sat down for a night I’ll never forget.

The door stood open to the dusty floor-to-ceiling vinyl collection that Alexander loved so, his friends taking turns flipping records and selecting the next album. We listened to the blues, jazz, and classic rock. Muddy Waters carried us through our first course; the sultriness of the saxophone through our second; and eventually, jazz so old school it, for a moment, transplanted the men in old, smoky jazz clubs where their friendships originated.

The wine loosened everyone up. I relished their stories, and they mine. Oh, the stories. It was getting late, but with a surplus of both local wine and bountiful conversation, it’s no wonder nobody called the night early. A fiber of mischief grew alongside the laughter and haziness. At some point, one of the men carefully examined the table—its patrons—and with a boyish expression said, “I have a vial of LSD at the house,” glancing around for the dinner party’s approval. Shocked, his wife turned to him, while the rest of us sat quietly, amused. He said he’d saved it for ten or so years—a remnant from wilder years gone by in a decade far freer than the current—and tucked it away for a special occasion, a night like tonight.

We all glanced back and forth, intoxicated just enough on both the moment and wine to consider amplifying the evening even more, seeking approval from our neighbors of our own approval of the idea. One by one, “I’m in.” “Me too.” “It’s been years, but hell, why not?”

Daisy intervened, “Have you all lost your minds? It’s midnight, and we’re really considering dropping acid? On the anniversary of my father’s death?”

Everyone bargained with her, “Precisely, Daisy! Imagine the possibilities. Here, celebrating Alexander’s life, in his home. I couldn’t have hand-picked a better coterie to share such a night.”

“As much as I support psychedelics, I just don’t think tonight’s the right night,” she went on.

Then we drank every drop of wine in the house.

The next thing I remember was waking to the sound of a coiled-cord phone ringing. God, the ringing. I looked around and realized I was in the tower, lying perpendicular across the bed, still dressed. The second floor of the tower offered 360-degree views through its old-fashioned, latch windows, all of which were open, sucking in the air in a thirsty fashion, seeming almost as parched as I was. It was morning.

I answered the phone in a haze, one hand tight over my forehead, attempting to hold the hangover as still as possible. It was Daisy. She was checking to make sure I made it back the night before in the drunken state I must have left in. Somehow, I managed the steep hike in pitch black, though I can assume it was more of a stagger or crawl. Whichever it was, it was long forgotten. We giggled about the antics the night before, “Can you believe we thought that was a good idea?”

It was time for the town’s farmers market, which we’d planned to visit together before I headed northward to visit my grandad’s final resting spot beneath a behemoth redwood outside of Orick (another story to be told). I pieced myself together, swallowed glass after glass of cold spring water, packed my things, and walked, for the last time, down that beautiful hill I’ve returned to many times over the years.

At the farmers market, one by one, we all streamed in from the night before, each of us in a similar state of hangover, subtle disbelief, and amusement. Far more poised than eight hours earlier, we all politely said hello, dusted off the slight embarrassment of how our nights ended. Then it was awash; we bought our morning pastries, basked in the sunlight, scratched the heads of the town dogs, and sipped warm coffee as local children set up for a play about the Civil War inside.

We said our goodbyes and extended hugs over a soulful, mischievous memory we all certainly carry with a smile. I bought a bouquet of peonies, drove past the Cockburn estate one last time, gave Jasper and the house kitty one last farewell, and headed north to say hello to grandad.

Patty Young | January 4, 2023

|

Hello Ashley,

I recently came across the story that you wrote about Alex Cockburn. it was wonderful. I knew him a little and actually I had a bit of a crush on him. How could one not. i miss the fact that his mind, spirit and body are not on this earth anymore. he was a good man.

I will tell you now that I am an atheist, hugely liberal and a globally known whistleblower. I’m the flight attendant who started and led the modern day non-smoking movement.

I started my flying career in the summer of 1966 when i was a week into my 20th birthday.

The first thing some of the other stewardesses told me was that I would meet very interesting men, go to beautiful places and that they had the lungs of smokers and that they had never smoked. They knew this because we had to have yearly physicals with american airlines to keep our jobs. This all was shocking to me.

Later these stew’s got lung cancer starting at the age of 27 and had never smoked.

it took 31 years to get smoking off the aircraft and the whoring was everywhere. The only people who helped us get smoking off of the planes were the democrats. The republicans stopped us at every turn.

I have a lot to say about this issue and about my fight if you are interested. It is a spectacular and very sad story.

My brother-in-law is dr. don carleton and he is the executive director of the dolph briscoe center for american history at the university of texas in austin and Alex cockburn gave all of his papers to don. I have too.

It might be good to put my name into google or into lexis/nexis so that you know that i’m not lying.

I’m up late most every night so if you would like to talk to me daytime or night my home phone is-214-357-6963 and my cell is-214-335-6963.

I prefer using my home phone.

I hope that you might be interested in my story.

Cheers and a happy safe new year,

Patty young

Ashley M. Halligan | January 31, 2023

|

Thank you so much for sharing this thoughtful story/perspective/and thoughts! I’d love to hear more! You can reach me at: ashley.m.halligan@gmail.com.

Sue S | January 15, 2023

|

what happened to your dog after the party?

Ashley M. Halligan | January 31, 2023

|

Timber and I continued our California roadtrip, venturing eastward to Gold Country, Tahoe National, and back down to West Marin. That was in the summer of 2013, and he died on December 30, 2014. So it was a great last big adventure together. 🤍